Looking Back to Move Forward

1968 Sanitation Worker's Strike

In the 1960s, sanitation workers in Memphis were almost exclusively African American. Memphis had a long history of segregation and classism in the wake of Jim Crow, and the evident work disparities of black sanitation employees in comparison to that of their white counterparts was indicative of the city’s racial inequities. Many lived in poverty and were paid only slightly above minimum wage for a ten-to-twelve-hour workday. African American sanitation workers often took on second jobs to supplement their income or appealed to welfare and public housing.

African American sanitation workers were excluded from the same benefits and protections as their white counterparts, enduring horrific working conditions. They often cited faulty equipment and a lack of enforcement of fundamental safety standards. Injuries were common, and there were incidents of accidental deaths in 1964 and 1968. The frustration towards the city’s long pattern of neglect, discrimination, and abuse of its black employees prompted the unionization of black sanitation workers who eventually led a labor strike in 1968.

The Murder Of Larry Payne

Larry Payne was a sixteen-year-old Mitchell Road High School student, and one of nine children born to Mason and Lizzie Mae Payne. Like many young, African American Memphians galvanized by a new wave of social justice activism, Payne was drawn to the community-orchestrated activism ignited by the Civil Rights Movement. He along with several of his classmates participated in the March 28th Downtown demonstrations that would eventually explode into violent chaos. In this ensuing chaos, Payne was confronted by Memphis Police Department Patrolman Leslie Dean Jones, who beat Payne before pressing the barrel of a sawed-off shotgun into his stomach, firing a single fatal shot.

Officer Jones maintained that he first encountered Payne emerging from the basement of the Fowler Homes housing development holding a large butcher knife in what he assumed to be an act of aggression. This statement would be refuted by several witnesses to the killing who reported that Payne had no weapon and raised his hands above his head, immediately submitting to Jones. Despite the overwhelming testimony of several bystanders that maintained that Jones’s shooting of an unarmed Payne was not provoked by any threat or criminal act, a Shelby County grand jury declined to indict him on any charges. The Department of Justice opened an internal investigation of the incident. Their findings would further exonerate Jones. They concluded that the insufficient evidence would not implicate Jones in either police brutality, racial profiling, or unlawful killing. In 2007, The Federal Bureau of Investigation opened a second review of Payne’s death, which included a reexamination of police records, court documentation, and newly obtained testimony of at least three witnesses to the 1968 events. The review concluded that both pre-existing and recent evidence reaffirmed that Jones’s use of deadly force when he shot Payne was necessary and justified. Payne’s funeral was held at Clayborn Temple on April 2, 1968, with approximately 600 mourners in attendance. Rev. B.T. Dumas delivered an impassioned eulogy entitled "Man Is Like Grass and Is Cut Down in Various Stages of Life” but made no reference to the circumstances of Payne’s murder.

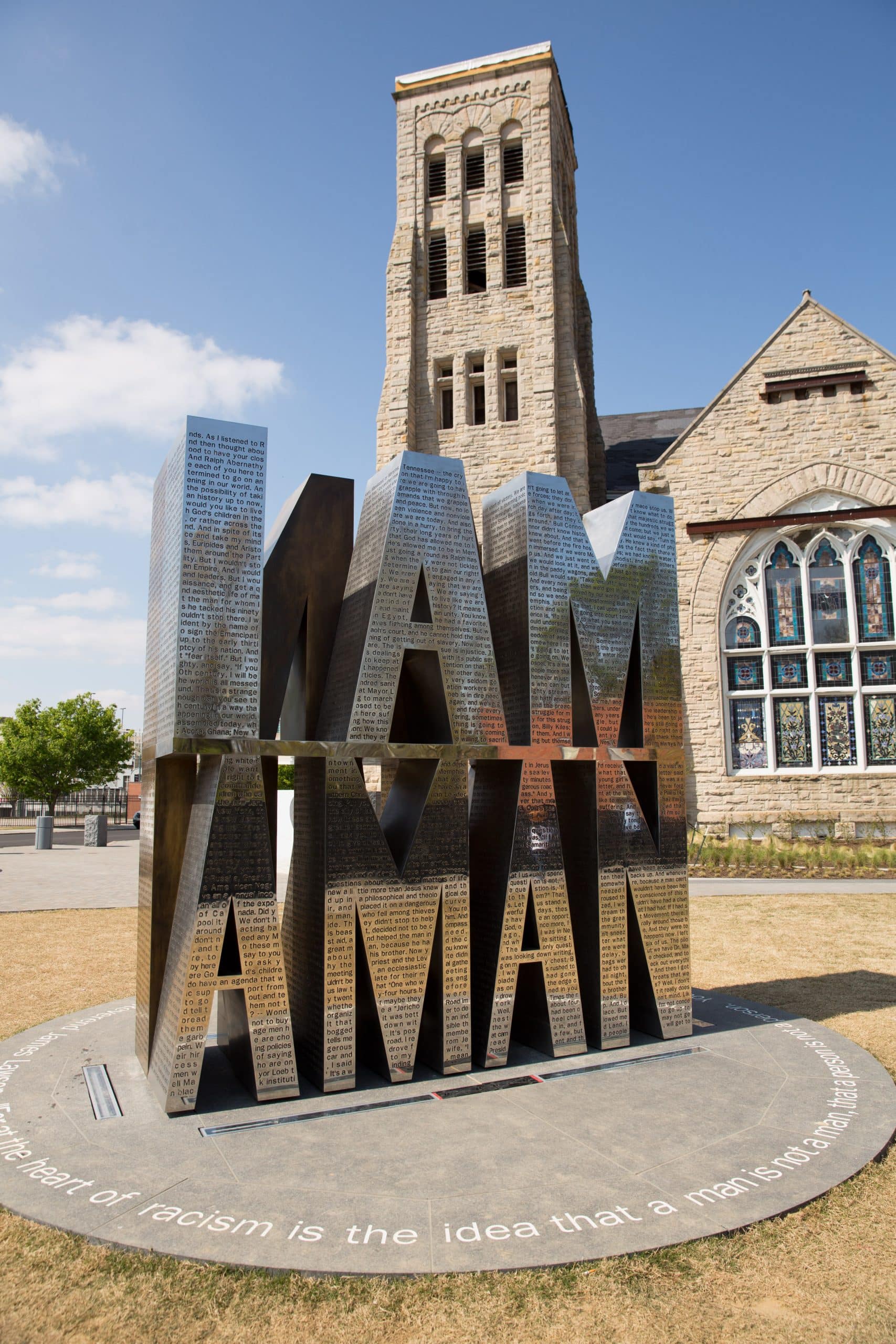

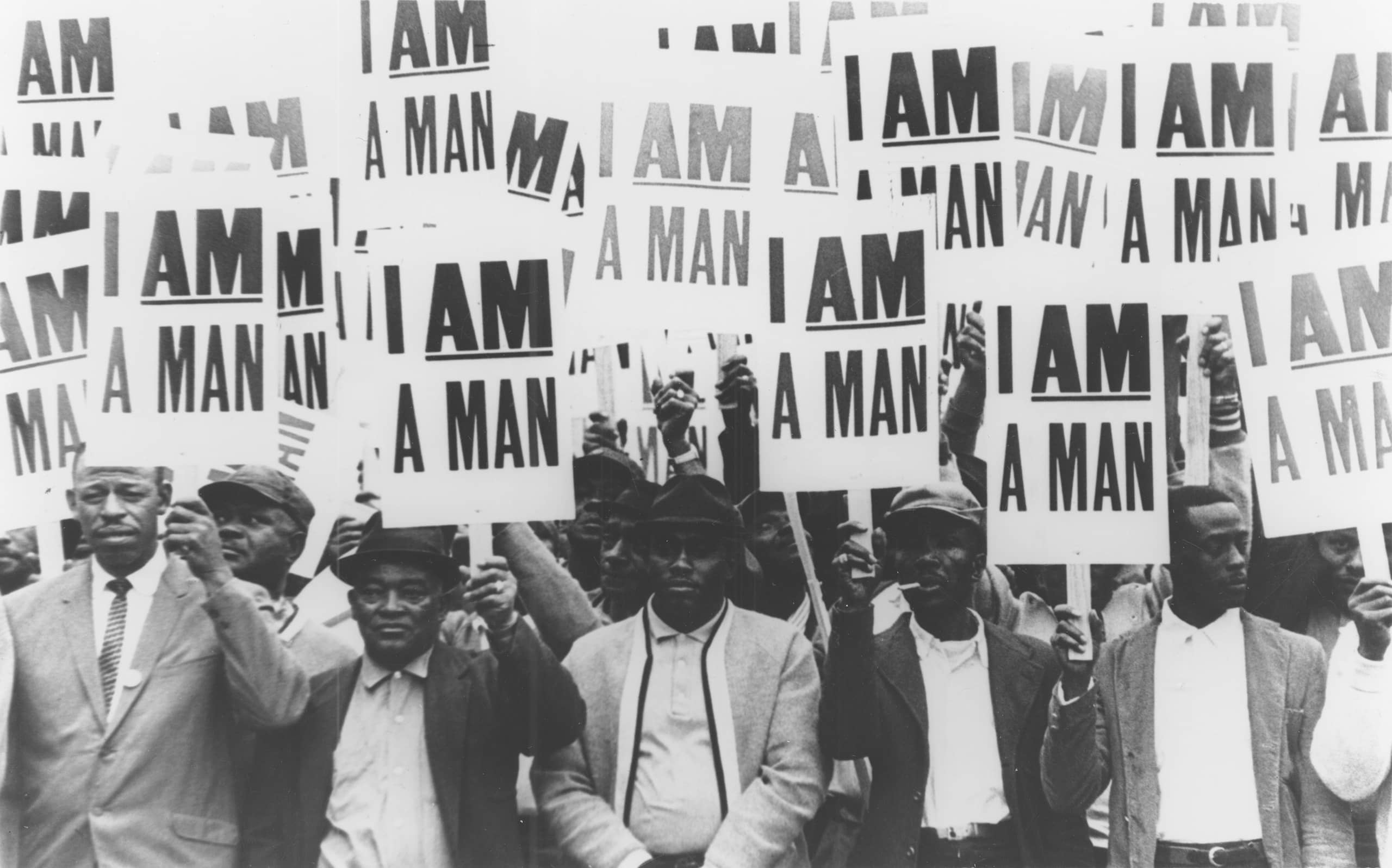

I AM A MAN Campaign

T.O. Jones

Thomas Oliver Jones (known as T.O. amongst family, friends, and colleagues) proved instrumental in the early stages of the 1968 Sanitation Workers’ Strike. He would maintain a leading position in the origination of union activity amongst African American municipal employees. Jones himself had been employed as a sanitation worker in the City of Memphis in the early 1960s and experienced the prevalent nature of racial disparities and prejudice in the Memphis Public Works Department first-hand; including a lack of enforcement of basic safety standards and unequal wages. After a failed attempt to organize a union in 1963, he and 32 other employees were dismissed from their positions.

Following his termination, Jones would fully invest his efforts into the arena of the labor rights movement. He continued to agitate for unionization. Becoming a representing figure in Memphis’s African American and public works community, Jones actively worked against the city's neglect, abuse, and exploitation of its black employees. Though Jones had successfully formed Local 1733 of the American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees (AFSCME) in November 1964, the city officials refused to recognize the union. Still, even without formal accreditation, Jones in his capacity as AFSCME president continued to gain concessions for workers and advocate for economic justice throughout the duration of the strike.